We were promised prosperity... instead we got SPAM

Ever since I can remember, I have had a pervasive fascination with the ubiquitous yet humble Asian market. As many children of first-generation immigrants can corroborate, I grew up with the idea that there was an innate link between the food around me and my cultural identity. It was one of the ways that the realization first came to me that I was different from others. I’ll forgo the tired anecdote of the stinky lunch box and the grating laughter of teasing children.

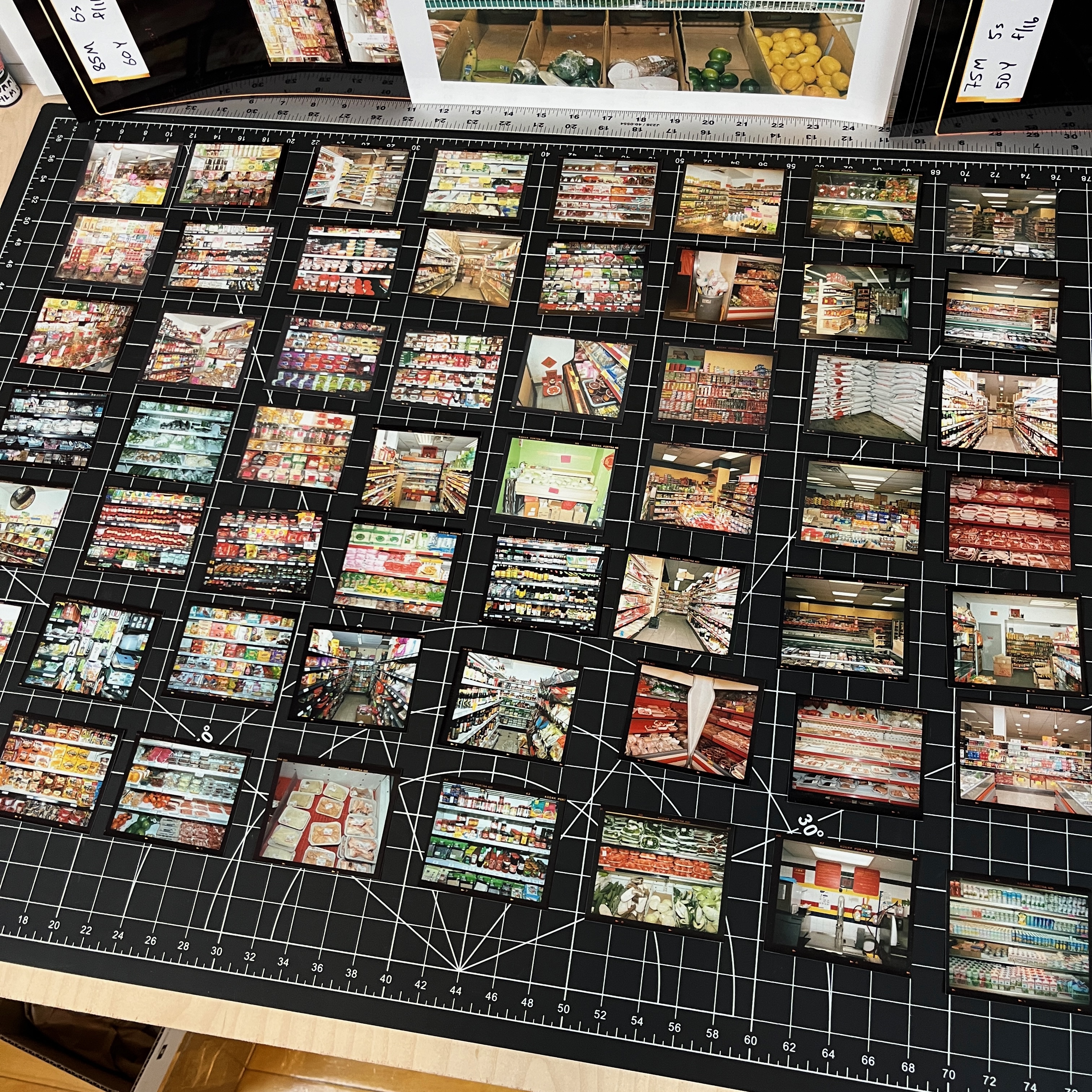

My memories of the weekly visits to these cultural gastronomic enclaves with my mother are early enough that the scenes place me sitting in the cart, facing backwards, my feet dangling. The colours and smells stream past like warp-speed star trails of silkworm pupae and pickled mustard greens. Immersed in the din of languages that crackled with energy and crisp, staccato-like enunciation, juxtaposed to the round, drawn-out timbre I heard from the tongues of my teachers and friends and neighbours and strangers and my own, sometimes.

In my dreams, I see round rectangular tins of SPAM sitting neatly next to stacked cans of water chestnuts and bright red bottles of Heinz ketchup beaming proudly next to fiery crimson jars of Lao Gan Ma.

The Americans gave us SPAM and their cheese and weapons and tactics. We made budae jjigae and crossed oceans, arms stretched out towards the promises of prosperity that beckoned and winked.

Generations later, in aisle eight of Lucky Dragon market, or H-Mart, or Kim Phat grocery, we gaze at neat rows of colourful sustenance and ruminate on the journey that a single tin of mechanically separated meat made through history and past fortunes.